How Better Beliefs Make Cognitive Biases Your Friend

How do better beliefs make cognitive biases your friend? Misunderstood cognitive biases reveal poor beliefs that limit performance. Three simple steps can be followed to improve performance. The first step is to uncover the faulty belief behind the misunderstood cognitive bias. The second step is to replace the faulty belief with a new belief that removes performance limitations associated with the faulty belief. And the third step is to determine and practice a new behavior that supports the new belief.

What is meant by a belief? Psychologist Dr. Michael Shermer describes a belief as a pattern we believe is real (https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_shermer_the_pattern_behind_self_deception#t-1121529). Dr. Shermer points out that our brains are driven to find patterns because patterns support our survival. Patterns also fuel our ability to learn or process our life and education experiences. Beliefs are patterns based on our accumulated life experiences that our brain has selected to store in long-term memory. Thus, beliefs reflect our unique interpretation of our accumulated life experiences.

Dr. Shermer also describes two ways our beliefs can be wrong. One way beliefs can be wrong is accepting a pattern that is not real. A second way beliefs can be wrong is rejecting a pattern that is real. In fact, the propensity for these two types of errors correlates with the level of dopamine in the brain. The lower the level of dopamine, the more likely you are to reject patterns that are real. Conversely, the higher the level of dopamine the more likely you are to accept patterns that are not real. In addition, the propensity to find patterns and create beliefs increases when we feel a lack of control or a lack of certainty. Thus, beliefs are unique to our experiences, a core part of how our brain works, and subject to error.

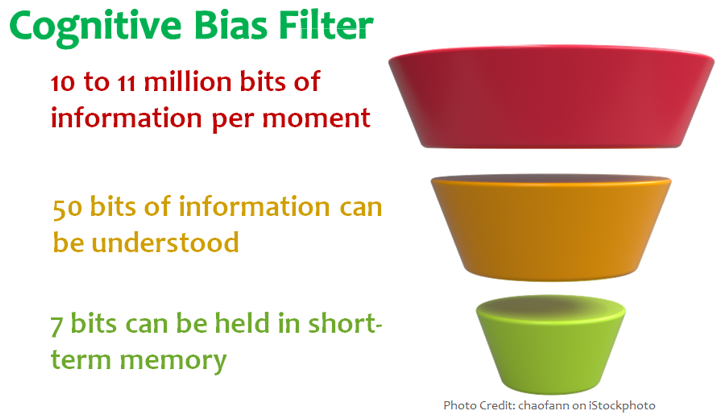

What is meant by a cognitive bias? Neuroscientist Dr. Julia Sperling explains that cognitive biases are thinking habits or thinking instincts – cognitive biases occur naturally often without our awareness (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vp60MMtJ_30). Scientists have discovered hundreds of cognitive biases that are fairly common across people (https://betterhumans.coach.me/cognitive-bias-cheat-sheet-55a472476b18). Cognitive biases are how the brain handles three of its most basic needs. The brain’s three basic needs are filtering, sense-making, and fast conscious processing. The brain needs filtering because billions of information signals flood the brain at any moment of the day while our conscious awareness can only manage a small fraction of that information. Neuroscientist Dr. Arne Dietrich explains the brain’s filtering challenge this way: “99 percent plus of all the brain’s computations occur in the ill-lit basement of the [non]conscious” (Dietrich A. How Creativity Happens in the Brain. 2015: Palgrave MacMillan, page 54). The brain’s need to filter serves two roles. One role is for the non-conscious brain to determine what fraction of incoming information needs our conscious attention. A second role is for the non-conscious brain to determine the fraction of information to store in long-term memory as patterns and beliefs.

The brain needs sense-making because we have a default thinking mode for how we fit into the world around us. Neuroscientists have discovered the regions of the brain that are activated when we are not paying attention to anything in particular. These brain regions taken together form the Default Mode Network. David Rock describes the Default Mode Network this way in his highly acclaimed book Your Brain at Work: “This network is called default because it becomes active when not much else is happening, and you think about yourself…..When the default network is active, you are thinking about your history and future and all the people you know, including yourself, and how this giant tapestry of information weaves together.”

The brain needs fast conscious processing because the region of the brain where conscious processing takes place has limited capacity. Conscious processing includes thinking tasks like decision-making, planning, and problem-solving. David Rock provides the neuroscience and behavioral science basis for our brain’s limited conscious processing in his book Your Brain at Work. For example, relational complexity studies show that the fewer variables you have to hold in your brain, the more effective you are at making decisions. In addition, memory degrades once you try to hold more than one idea in your mind at a time.

This post shares a personal example of how thinking about a cognitive bias called curse of knowledge led to an opportunity to improve performance. Curse of knowledge is a type of cognitive bias that helps us with sense-making. The curse of knowledge bias is our tendency to rely on our knowledge to make sense of the world even when we are interacting with others who don’t have our same knowledge (https://hbr.org/2006/12/the-curse-of-knowledge).

The first time I heard about the curse of knowledge was in a communications class at work. My reaction to the concept was as follows: “Oh! Curse of knowledge explains why I and other scientists are poor at communication!” I took this new concept called curse of knowledge and used it to confirm my existing belief that scientists are poor communicators.

The next time I thought about curse of knowledge was for a speech I was giving about collaboration. This time I thought that curse of knowledge explains why scientists have a hard time responding effectively to others who criticize science findings. Again, I was using curse of knowledge to confirm my belief that scientists are poor communicators.

The third time I thought about curse of knowledge was in the podcast interview with Jill Schiefelbein (https://fulcrumconnection.com/blog/026-avoid-disaster-technical-organizations/). I wouldn’t say the third time was the charm – I would say the third time was painful to my ego. Jill said that the more knowledge and expertise you have, the better you are able to communicate effectively to all audiences. Woah! Jill’s perspective on the curse of knowledge revealed my incorrect belief that scientists aren’t good communicators with non-scientists. My incorrect belief hinders my ability and the ability of other scientists to communicate effectively with non-scientists. In fact, the more knowledge you have, the better you are able to communicate with those outside your area of expertise. So scientists are poor communicators only because they choose to be not because they don’t have the ability to be outstanding communicators. A new belief that empowers scientists is that scientists have the content for outstanding communication and just need to learn the process to be outstanding communicators. The communication process skill I have elected to work on as a result is making my writing more succinct. Hopefully this post is a good illustration of some progress on this skill! The next time you realize you have a misunderstanding about a cognitive bias, think about the belief behind the misunderstanding. Is the belief empowering or limiting to your performance or the performance of others? If the belief is limiting to performance, then what new belief would be empowering to performance? What new behavior would best support the new, empowering belief? How can you practice this new behavior enough times to make the new behavior a habit? Keep in mind that it takes an average 66 repetitions to make a new behavior a habit (Lally P. et al. “How are habits formed: Modeling habit formation in the real world.” European Journal of Social Psychology. October 2010: Volume 40, Issue 6, p.998-1009). Please share your perspective on the curse of knowledge bias and other cognitive biases by commenting on this post.